When History Refuses to End

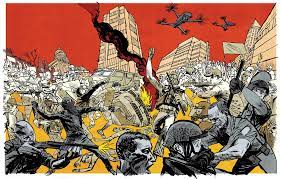

Today, many people feel as if the world has slipped back into one of its darker chapters. Whether it is Ukrainians resisting Russia, ordinary Russians caught in the consequences, the peoples of the Middle East, or even societies living in comfort, Europeans, Americans, and their allies, everywhere you look, communities are going through a severe test. The problem is simple to name but hard to solve: everyone suffers. Most of the world lives in poverty or without basic security, and there is no sign that this will change soon. Wars, conflicts, and political schemes continue under the banner of “state interests,” yet it is ordinary people who end up paying the highest price.

In such an atmosphere, identifying the roots of these problems becomes essential for understanding how they might be resolved. In the 1990s, after the end of the Cold War, many in the West grew confident that their own model, along with their values, would be embraced almost automatically by other societies: by the peoples of the former Soviet space, by the cultures of the Middle East, and by communities whose historical paths had been shaped in entirely different ways.

This was, of course, a serious misconception. I wouldn’t argue that the opposite course should have been taken, or that Western policymakers were obliged to adopt a completely contrary strategy. Yet expecting Russia—and many other states—to shift rapidly into capitalism and internalize liberal economic values was a strategic mistake. In this sense, Francis Fukuyama’s End of History thesis appears as a hypothesis built on the assumption of the West’s unquestioned superiority.

Had a more cautious optimism been adopted instead, the transition of these societies into the liberal world might have unfolded more smoothly. If cooperation had been built in a way that respected the cultural frameworks of each people, many of the crises we face today might not have emerged. It is quite evident that what irritated Russia’s post-Soviet elite, what pushed political Islam from a marginal movement into a broad, mass-level response—at least for a time—and what eventually turned into one of the West’s biggest headaches, was this persistent belief in the superiority of its own values.

I do not want to reduce historical dynamics solely to this phenomenon. The way the West appeared in the eyes of these societies, their own historical trajectories, their cultural and even religious values, their attitude toward modernity, and their collective sense of friendship and enmity all played a part. Even so, in the early 1990s the West possessed an extraordinary level of power—ideological, economic, political, and military. In my view, if that moment had been used not to draw new lines of division or to cultivate new adversaries but to build a more inclusive form of cooperation, without projecting any sense of superiority, many of the problems we face today would likely have taken a very different path—perhaps they would not have appeared at all.

Yet the world still has a chance. Making it livable for everyone is not an impossible ambition—whether through reforms to the UN Security Council or through more responsible behavior by major powers. I know this may sound somewhat utopian, but there is no alternative. The opportunity wasted some thirty years ago, and throughout the decade that followed, does not have to remain lost. It is still within our reach to stop the bloodshed in the Middle East, in Palestine, Sudan, Libya, and in the war between Russia and Ukraine. We can still build a world that belongs to all of us and is shared more fairly—if there is the will, and if there is genuine good faith behind the effort.